About six weeks ago, we decided to extend our stay in Nepal for another year. As a result of that, Luke and I need to do more language and cultural training. We didn’t do any full time language training initially, as we were staying for such a short time. For the past four weeks I have been doing intensive language classes and study. I have two hours Nepali lesson each morning and then a few hours of revision an homework each afternoon. I am relieved to be returning to “real” work on Sunday, as my brain is now officially full.

In the last four weeks I have probably covered almost as much as I did in my weekly lessons prior to that. I learn verb tenses and constructions in order to make it easier to say things I wish to. Of course covering them in class is not the same as learning them, and I spend three to four hours most days practising and revising. As I am pretty shy to speak generally, the real value has been to spend two hours each day speaking as much as I can with my teacher.

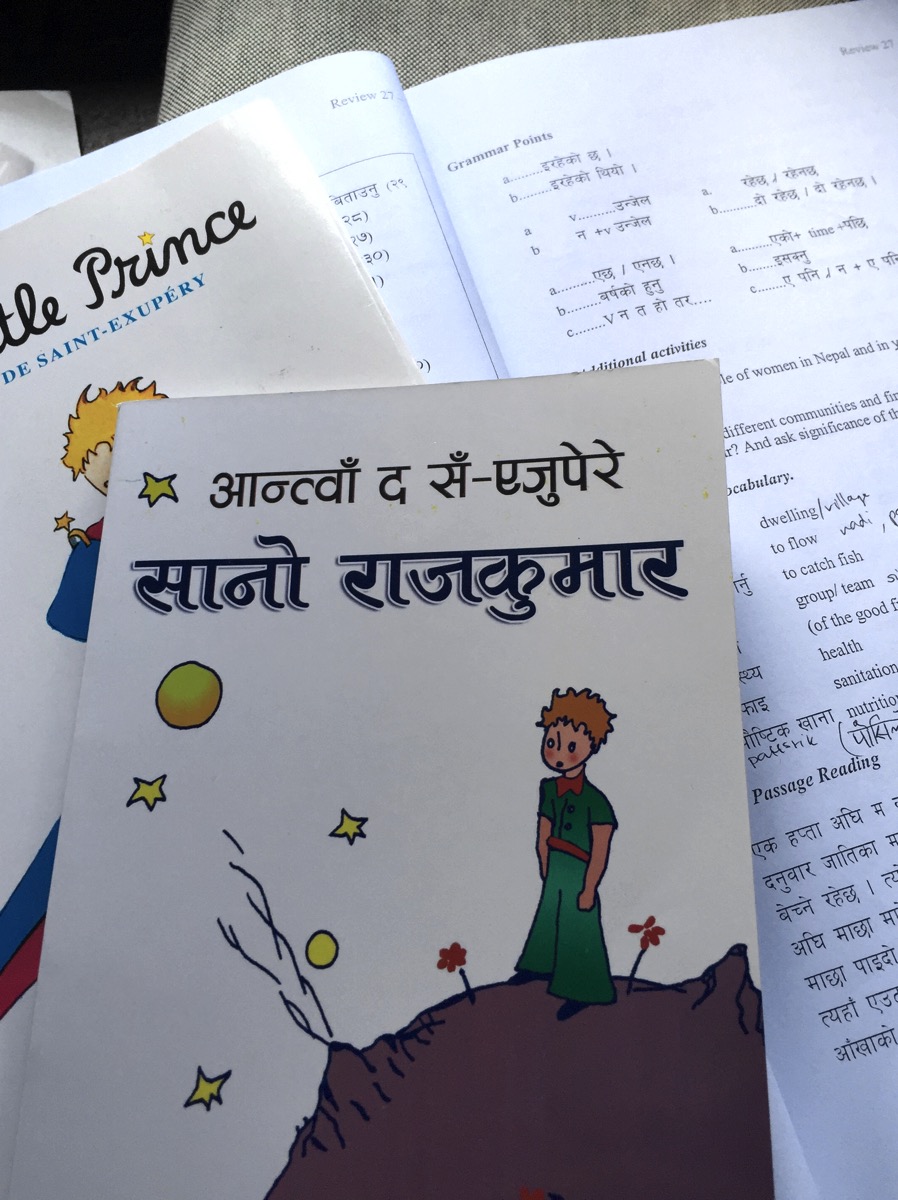

For those who have not lived here, Nepali is spoken primarily in Nepal, India, Bhutan and Myanmar and is written with Devanagari script. It is closely related to Hindi and often Nepalis can learn to understand Hindi without formal lessons, just by watching movies or TV. For English speakers, Nepali is rated as a more difficult language to learn, with significant linguistic differences from English. Some of these no doubt relate to the different script, as Nepali is relatively regular and phonetic, with few irregular spellings and conjugations.

However, there are some things that I still find difficult:

- There are eight similar phonetic sounds in nepali, romanised as Ta (ट), Tha (ठ), ta (त), tha (थ), Da (ड), Dha (ढ), da (द) and dha (ध) that Nepalis hear as very distinct sounds. The two versions of each sound are created in different parts of the mouth – one just at the teeth and one at the back of the hard palate. Mixing them up completely changes the meaning of a sentence.

- The character व, however, can be pronounced “wa” or “ba” and no one really seems to mind which one you choose. There are conventions, but you basically have to learn which words use which sound.

- ब is also pronounced “ba”. Yep.

- There is a special construction of verbs to describe seeing or doing something for the first time, or when something is unexpected.

- Whenever an english co-opted word starts with the letter “s” it gets a quick “i” sound added for free – “i’school”, “Dr i’Steve”. No one can tell me why. Nepalis are very generous with syllables: when in doubt, add one.

- There are no capitals letters in Nepali script, so when reading Nepali script I can struggle through a word and feel completely confused by it, without realising it is a place name.

- English words in Nepali script look very, very strange. They tend to follow different pronunciation rules than standard nepali words, so I find those words the hardest to read.

- Nepalis send text messages and write Facebook status updates in romanised script, with no convention in spelling. And sometimes half the words in english. They have no problem understanding this, but my brain is stuck in a single language mode.

- ba and wa. I mean, really.

Of course, learning Nepali in a mission hospital is different to learning it anywhere else. Not only do I learn “How are you?” and “My name is Cris”, but I also learn “Show me where the pain is”; “An operation is required” and “Don’t eat any food, please.” Furthermore, I am learning the words for “resurrection” and “forgiveness” and “raise form the dead” which I don’t remember learning when I learnt German at school!

I write a lot about language at the moment, because it is one of the focuses of my work here – deciding when and how to operate is less difficult than understanding what symptoms a patient has. The silent partner in all my musings is our hospital language teacher. He has worked for UMN as a language teacher for eighteen years, as long as I have been married. Since I arrived in Tansen, I have had four hours of lessons a week with him, and he has dragged me forward from simple words and sentences to much more complex constructions. It takes me about 3 minutes to construct a sentence, and he patiently waits for me to prove the words are all there in my head, and barely flinches when I crash through the verb conjugation at the end.

Although I love, and am passionate about surgical teaching, I can’t imagine patiently correcting embarrassing language gaffes, clunky accents and misunderstandings. I salute my teacher for all that he tolerates, his patience and his fortitude. And for accepting the cups of tea, and questions about politics and culture that we all use to get a break in lessons. Thank you, Khila.