It is easy to become accustomed to low cost surgery. What seemed bizarre to begin with, seems pretty ordinary now. So this post will be a compilation of photos to explain a typical laparoscopic cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder) in Tansen hospital.

As I have explained before, there is no long waiting list for elective surgery in Tansen. If patients need an operation, we book them in on the next slot, which is usually in the next few days. In order to have any “large” operation performed, patients need to provide one blood donor who donates a unit of whole blood (patients who genuinely have no relatives or neighbours are exempted). For cases like lap choles, this blood is very unlikely to be used for the patient, but it forms part of their payment. It is added to our stock to be used for emergency patients when required. Along with blood, the patients pay for their operation and hospital stay (about $200-300 US), and need to provide a family member who will look after the patient while they are in hospital, fetch their food from the cafe (or outside restaurant) and help them to the toilet and to mobilise etc.

The main difference with our operating suite is the lack of money for single use items. This generally means we operate a lot more like MASH and a lot less like “ivory tower” hospitals.

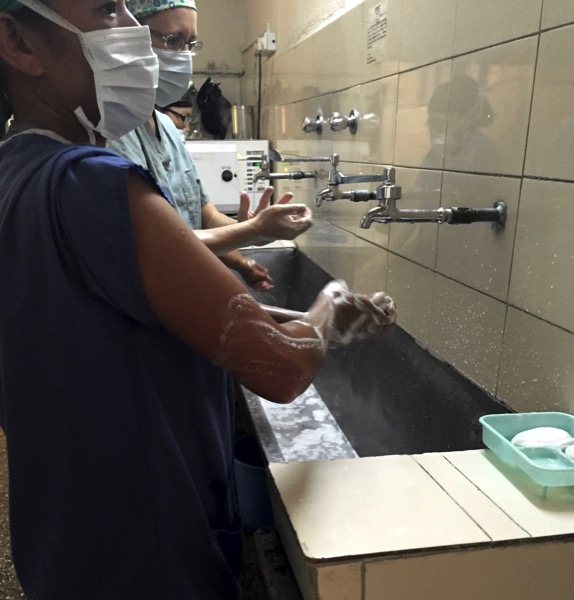

We wash in the sink, with soap.

Our instruments are a mishmash of reusable and single use items. Almost all are donated. All the single use items get resterilised and reused regularly. The nurses setup is very simple. The gauze pieces get cut and packed, and sutured together before sterilisation – nothing is purchased pre-sterilised.

We only have one automatic ventilator, which is na recent addition, so often the anaesthetists (actually anaesthetic nurses, not medically trained) have to hand ventilate throughout the case. No surfing the stock market.

Our laparoscopic ports are also reusable, and we use sterile covers on light and camera leads. These items can be sterilised, but we are careful as our power supply is variable, a combination of generator and town power, that sometimes dips and surges like a mountain range. Laparoscopic equipment is too precious to risk, so we use covers.

Unfortunately, we do have a relatively high conversion rate for cholecystectomy. Patients arrive late for surgery and have quite inflamed, scarred gallbladders. Also, we sometimes convert to open for technical problems, like electronic equipment malfunctioning. In Melbourne I never would have considered to the need to convert to open just for recurrent power surges or a malfunctioning UPS (which keeps the stack running when the power is out).

Our operating tables are radiopaque, which makes operative cholangiogram difficult. When we know there are CBD stones, we have no capacity to remove them laparoscopically, so we choose open CBD exploration – an operation I learnt for my exam, but never had to perform in Australia.

Nepali patients recover very well after surgery. They are strong people and are typically used to working despite pain, and are rarely precious. It is not uncommon for patients to have to walk one or two hours home from the main road after their operation, so we keep them a few days if they choose to stay – almost as caring as a private hospital back home!

I know the surgeons and surgical nurses amongst my readers will see the difference in our setup compared to a medicare funded system in the first world. I’m sure my non-medical friends can look through these photos at the rooms we work in and realise our hospitals at in the first world don’t look like this. But despite all that, this operation, and many others like it, are a link between the two settings. All patients across the world need surgical services, and without them, their life would be shorter and of poorer quality. Despite obstacles of poverty and resources, we can provide appropriate “best practice” surgical treatments, equivalent to what we would offer at home.

And even more exciting, we can spend time training the junior Nepali surgeons to provide the same surgery. If our laparoscopic capacity was lost, we would still be able to treat patients. But the guys in this photo who will be surgeons in Nepal for the next forty or fifty years would lose the chance to learn laparoscopic surgery safely. It is possible to perform “advanced” surgery in a low cost way, with cheaper equipment and less disposables. Although we daily make decisions about utility and value, we are proud that we can perform laparoscopic surgery, and our arthropods can perform joint replacements and spinal surgery, at a high and reproducible quality.